This is the 16th installment in my series, GENEs where I interview locals I have met over my time taking photos in “east vancouver” and unravel the stories behind their favorite things.

To check out the previous interviews covering a range of clothing with innate gorgeous stories, see the link here.

To ensure you don’t miss an interview, please consider subscribing.

For the first phase of this project, I’ve stuck to using my own voice to summarize, distill, and tell the majority of the story of my interviewee. As I mentioned in the introduction episode of this next “audio format phase”, I do this intentionally, mainly, to ensure that there is a chance for me to think about the interview and general narrative, but also to allow the interviewee to preview the “final product” before publishing.

For this interview, in an attempt to continue to grow in a new direction, I wanted to give the guest the space and time to talk, and this guest was the perfect transition from the style of interview I am moving towards.

So for this episode, you'll hear less of me, and more of my guest. and I think you'll really enjoy it.

This is definitely one you want to take the time to listen to, to hear the language and to really understand the stories that goes into his art.

Let's get into it.

I started the interview with asking him simply: “who are you, and what has brought you to where you are today?”.

Oki Niitaniko Naatsikapamatoosin, nomohtootoo Siksikaitsitapii Piikani, ki Kainai, ki Siksika, kiitsiksimatsitsi xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish), Sel̓íl̓witulh (Tsleil-Waututh).

So usually when I do an introduction, I introduce myself in the Blackfoot language, and that's what we call it. And I just introduce myself and said, Hello, my Blackfoot name is Naatsikapamotoosin, which means Two Smudge which was given to me by the late Louise Crop Eared Wolf. My English name is Matthew Provost. And I just acknowledged where I come from, so that would be the Blackfoot Confederacy. And on my maternal side, my mom were from Piikani. On my dad's side, we're from Kainai, the blood reserve. And then my grandma, we have family in Siksiká.

Born in Treaty 7, Southern Alberta he moved to the city of Lethbridge and started school there when he was young as his mom moved for work. He grew up between the Indigenous reserves where is family resided and going to school in Lethbridge. He found himself interested in clothing from a very young age, inspired by skate culture through magazines. In high school, he wanted to pursue more artistic pathways, but unfortunately, was never given he opportunity. He found himself being directed more towards trades and skills work in his course selection by school councilors, which he still looks back on with some sadness and resentment. He was very grateful though that he was able to take Blackfoot class, and learn the history and language of his people.

As he moved towards the end of high school, still wanting to peruse art, he applied to the Visual

College of Art and Design without a portfolio, but was able to advocate for himself and his passions over Skype, and got he in. The following August, he moved to Vancouver and started the fashion design program where he learned to pattern draft and sew, among many other skills. He graduated from there, but then wanted to pursue one more program, as a back-up plan.

After I graduated I wanted to make sure that I had a backup plan. And so I decided to do my BA at SFU. So I applied, and then I got in. And so I finished that up, and it really opened up my perspective to the academic side of research. I did my major in Indigenous Studies and Public Policy and Governance and Relations. My minor was in communications; the political economy of communications. Now, when I'm doing design or art or anything, I always take a research approach to it. I'm always reading or looking at stuff or being observant. And then also, if I'm working with people, focusing on morally and ethically, making sure that people are paid or supported or really bring in that community perspective to support. Because my work, anything that I do, it always incorporates other people. It's not just me. And that's something that I've learned in that process of making stuff is it's not just a solo thing, especially when you're doing Indigenous art or design.

There's a whole background of community that people see, whether it's a collection or an exhibition or a small project. There's all these other things that come to support what's happening. So I think a lot of that came from going through all those experiences and being where I'm at now, where I'm like, after I was done school, I was like, all right, I'm going to work and I'm going to focus, and go back into doing art. So I didn't sell for a really long time. After a while I got to get back into drafting my own patterns and stuff. So it was just retraining that muscle. If you're doing it so much, then when you take a hard stop at it, you forget. But then when you start going, it's easier. So I was like, hey, I want to do like Vancouver Indigenous Fashion Week. And that was a goal that I set out for myself. So I did that. And then trying to focus on where can my practice go into? And I like all different forms of mediums. So if I think that I can learn it or do it, I'll try it because I don't want to just be stuck in.

It's good to be really good at one thing. But for me, my attention span is so small that I just want to be interested in a lot of things. And then I can incorporate into what I'm doing or also build an appreciation for what other people do on that one skill because it's not something that's learned. People spend years and years and years doing this. So even if I'm able just to learn a a little piece of it and incorporate that. Then it helps build what I'm able to do.

Two Smudge is a multi-disciplinary artist, pushing himself in all forms possible. In following him for the past few years I've watched him move from having collections at Indigenous Fashion Week, to print making, producing clothing, and having art shows. He just finished an art show at Crack Gallery and prior to us meeting, he was reflecting with a friend on the thrill of taking on new mediums, and the challenges that it presents. He had also been reflecting on how collaboration and community pushes him to be able to accomplish it all.

I find that there's always a point that you reach when you're trying to do something and you almost feel like you can't do it or you're not going to finish or you're not going to make that deadline. Or it's just so, I don't want to say frustrating, but it's almost intimidating. And that's where I get a lot of imposter syndrome still. And then I'm like, well, fuck, I have to do this. My name's on this thing. I have to finish that commitment. We have to make this work somehow.

You just put yourself in overdrive, where you're It's like running on no fumes, and you just focus. I need to get to my end goal of just getting this done regardless of how it happens. And I find that's when you see a lot of growth as an artist or someone who's in design or creates things. It's just when you're burning it to the wire, that's when you find the most growth.

I was able to finish it, and I can do it again. And you know that you're capable of more things. And the last few years doing that has really helped me as a designer, but also experiment with other mediums that I want to pursue. It’s to learn more for myself and to just have more knowledge and understanding about things, but also to figure out what components work together, what don't I like, what do I like? What do I want to do? I feel like that's where you see the most growth because I feel like everybody feels like that at some point when they're doing stuff.

Immediately after this connection over our mutual desire to try different avenues of creation but always having the imposter syndrome around the corner, I knew we were going to be heading to interesting places in this conversation.

In preparing for the interview, I read about his process and inspiration for his fashion week pieces, so I wanted to know more about the imagery he chooses to appear on his clothing, and if he had any future ambitions to release his "workwear" as a broader collection. He walked me through what he is currently thinking about integrating in his clothing, and how he wants to continue educate through the deep meaning he places in his designs.

So I think, when I try to do that with the motifs or being able to do that into the work wear, whether it's the style or the design, the colorways, those are things I have to consider. One thing that I would really like to try is we have certain paints or colors that we use; so being able to dye it to that specific colours. If it was a canvas or a denim, being able to dye it to a specific tone of red or the specific tone of yellow, the same color that we use for ochre or paints, and being able to do things like that and experiment, those would be things that I would be interested in trying. And I think also being able to have access to try and do more intricate applique work. That's what it's called when there's a layering of fabric to create a design on things like that. Being able to have, whether it's different types of fabric or different types of layers on one specific, whether it's a jacket or pants and stuff. I really want to try that on pants, but to make sure that it lasts.

So when I was doing the applique, those are ones that have always stood out to me. Those are star designs, almost. They're our constellations. There's one that almost looks like a hook, it's like a curve. But there's seven there, and they call that one the Seven Brothers. That's pretty much our interpretation of the big dipper, how it looks like that. So when I'm able to show that, even if someone doesn't understand what they're seeing, for someone who's Blackfoot, they would be able to see it and be like, “Oh, I can see myself in that”. Those are things that I would want to try. One, to engage younger generation, especially younger men who want to do design, Indigenous men, because there's very few... I think there's more now, but being able to get them interested in clothing or making clothes or things like that.

But also for elders and stuff, they get to see that, and they've never seen it in that way before. So it's a different experience for them. And they understand the meaning behind it, but they get to see it in a different way than how they've seen it before, whether it's painted on lodges or done in a more traditional, whether someone painted it or whatever, just things like that.

Do you lean on a lot of historical reference from designs that you've seen from home?

Yeah. My family They used to vend. They used to vend at powwows. They used to be food vendors. So my family, my grandparents, my mom, they'd all set up this booth to sell tacos or food all weekend. And that was the big thing. And my family would come down from Siksiká, and they'd be there all weekend. But when I was younger, I remember, I was four or five, and I was walking around the powwow, and I'd see teepees, lodges. And some of them wouldn't be painted, but then some of them would be painted. But those are some of my first references of seeing those designs. And I don't know if I've ever thought about it as art. I just knew that that's what it is.

That's someone's home. That was my understanding of it. It's more than just... I don't make things to sell things. I don't make things to make money. I make it because it helps me learn, and I hope that it helps other people learn as well, and however people experience the things that I do, I hope they're able to take something away.

But being able to participate back home for cultural or ceremonial events and things like that really elevate the work that I'm able to because I have a better understanding of what I'm doing as well.

It keeps him connected too.

Yeah, exactly. And that's a huge component of that is not feeling disconnected in a way where I'm still making the effort to learn. It's not just like, Oh, I'm stuck on this one thing, and I'm just going to do it this way, and I'm not going to ask questions, especially from elders or people in community back home. I think that's a really important component for work that I'm doing is there's also a proper way to go through protocol. When I talk about protocol, my understanding of it is just…it's a set of rules or guidelines that we follow in regards to respecting something. So whether that's a cultural item or a person, an elder or something, there's protocol. All that's set in place so that we just follow that to show respect. That's how I understand it. But there's protocol in the way that I do my art or design as well, so that I'm not just co-opting designs. I've taken the time to learn, and it's taken a lot of research and a lot of just listening, and watching, and observing, and also being connected to community back home.

And I make sure that those relationships are strong and that they're ongoing and I'm able to lean on those if I need to ask or if I need to figure out something, because like I said, the stuff that I do, it's not just me just doing this.

It's a whole bunch of people helping me to do what I need to. Those are things that I think are important, especially with my practice. It's a little bit different because sometimes, even for me, it's sometimes hard to wrap my head around, but I know that It was a responsibility for myself to also learn about these things and not just do them without knowing what they are.

We continued to talk about some of the people and places that influenced him along the way growing up. His uncle, being an artist as well, pushed him and inspired him to draw. Living and working in his community gave him the tools and reference material that has now informed many of the designs and produces today. He mentioned participating in pow-wows and ceremony a couple times and I wanted to know more about these types of gatherings and how they develop his understanding of his art. The importance of paying respect to the protocols of his community, which will come back later in the interview, play a key role in how he thinks about his approach to being a Blackfoot artist.

It was so clear to me while we were talking that he takes great care in respecting the artists and culture that came before him, talking about the protocols with reverence. Sustainability has always been a theme in my conversations, and we talked about it with regards to clothing for sure, but there was a more important aspect for that resonated with me regarding that word during this interview. The idea of preserving his culture in a respectful and authentic way, keeps it sustainable, rich, vibrant, but also sacred, and I loved hearing about how being present for his family, and ceremony, impacted his connection to his people in a sustainable way.

It was then time to get to his chosen item, the central aspect of all of these interviews.

Turns out, I had been staring at it the entire time.

So I was thinking about... what is one thing that I would wear every day or something that I guess was super prominent? I've always had a hat. I've always worn a hat. I still wear hats, even for pictures and stuff like that. And everyone's like, Oh, why would you wear a hat in that picture? But it's just, I don't know, even when I was small and there's pictures of me, I've always had a hat. And I think that's the first thing I also spent money on when I was able to or if my family were like, Oh, what do you want from them all? I'm like, Oh, I'm going to go pick out a hat and get a 59FIFTY flat brim. And so I had a whole bunch of those. I don't know where those ones are now, but I've always just had caps. And one thing is I always get them when I'm traveling around. So when we go through the States, we've driven all the way down to New Mexico, and we've driven all the way around. So I'll get those farm team hats from the baseball. Or if I'm going somewhere and we went to I think, for example, me and Jess, one of our first times that we traveled together, we went to Seattle, and we got these scalper tickets to go see Seattle game.

And then so I was like, Oh, I'm going to buy a hat. So Those are just things. And then so it connects a memory to a place. And same with my grandpa. My grandpa has so many hats just from different racetracks he's gone to, everywhere, Los Alamedos, Emerald, Emerald Downs. Here, I got him one from here, even Saskatoon, all in the States and stuff. So I think that's something that I just picked up from him. It's like where we go get a hat. My uncle's like that, too. He went down to San Diego. I'm like, Oh, can you give me a Padre's hat? When you go down there. So he got me one and shipped it to me for Christmas. So it was just something that when I look back at it, it's like all my uncles, my grandpa, my dad, is something that we just all had, and I feel like it's pretty versatile.

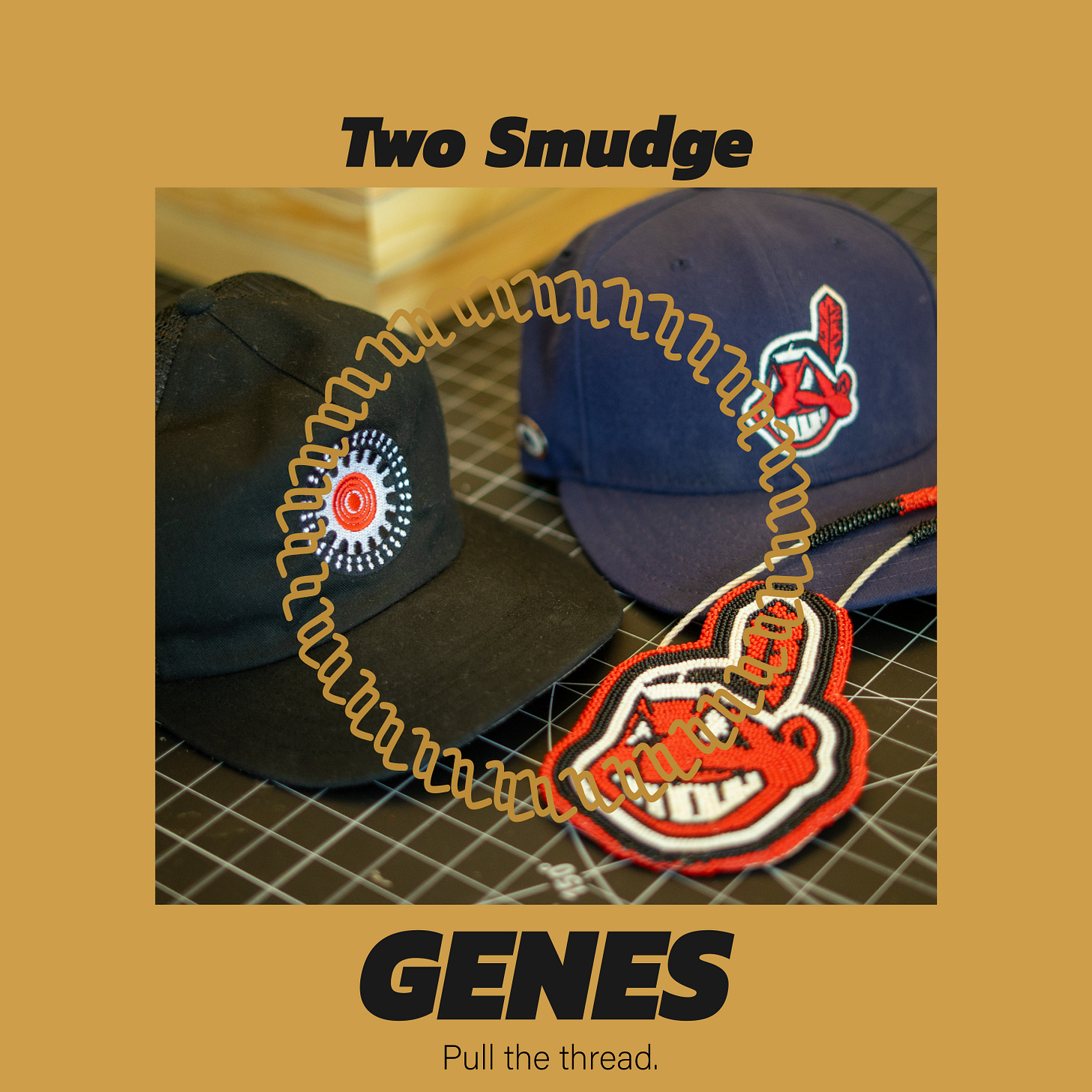

Of course, as I've been learning in talking with Two Smudge, the depth and complexity of meaning ran deep in his relationship to his hats. He mentioned he had a large collection, so I was curious if there was one that was his current favorite. He placed two in front of me, one, the one he had been wearing when I arrived, was the all blue Cleveland Indians cap. The second, his collaboration hat with Themme and Crack Gallery. He started explaining the process of the Crack Gallery hat, in collaboration with his friend Teen, and the roots of his affinity for the Cleveland Indians hat.

I snapped some photos and wanted to know more about the logo he had designed for his collaboration hat.

We were thinking about the hat we wanted to make and it was more like a trucker style because he (Teen) told me, “I wanted to be like something like your grandpa would wear”. So that's where that came from. And so my grandpa has this hat. And then so we gave him one. And the Cleveland Indians one, when I was 14, my mom asked me what I wanted for my birthday. And I told her I wanted a beaded medallion of Cleveland Indians. And so I still have it. It's upstairs. So I wear the hat and the medallion. And I always find different pins and stuff, too. So I'll put them on. But I just think it's a really versatile accessory. And that's something I don't really leave home without. It's a hat. And it's called Niitoyis. And the way that I thought about it was when you lay out a teepee, it's like a half circle because it makes a cone, almost. I was like, I wanted to see what it would look like if you're looking at from top down.

It was like a full circle flat. So that's where I took that from. And so the bottom is the foothills. That's where I grew up, the foothills. And then that is the Wolf Trail, those red lines that go across the Milky Way. So that's been a staple design, I guess, that I feel that I really represent well because that shows my home. Niitoyis means “my home”. So that's my home. When I look at that and those designs and stuff tie me back to who I am, where I'm from, and just that continuation of learning those things. So that's where this design came from. And trying to have all those components and to learn about it, to really understand it, and to share that protocol. Those are things that I want to share. And it's okay for some kid who's like, I want that hat. It looks cool. They can wear it. And hopefully, that triggers some deeper meaning that they're like, Yeah, an Indigenous artist made it. They're Blackfoot. And it's just sharing that imagery so that other younger Blackfoot people can feel connected in that way to knowing that their culture is still alive.

There's so much that is out there to learn and that hopefully pushes them to want to know more and want to do more.

He kept pulling out all types of hats, collectible Canada Post colorways, rodeo souvenir hats or baseball team lids him or his family picked up on their travels. He mentioned his grandfather also had a large collection of hats, and I was in awe again at another interview in which the item in question is literally in the DNA of the person. We went through a few more hats and I noticed a few art pieces on his desk, so I checked in about his show that had recently happened.

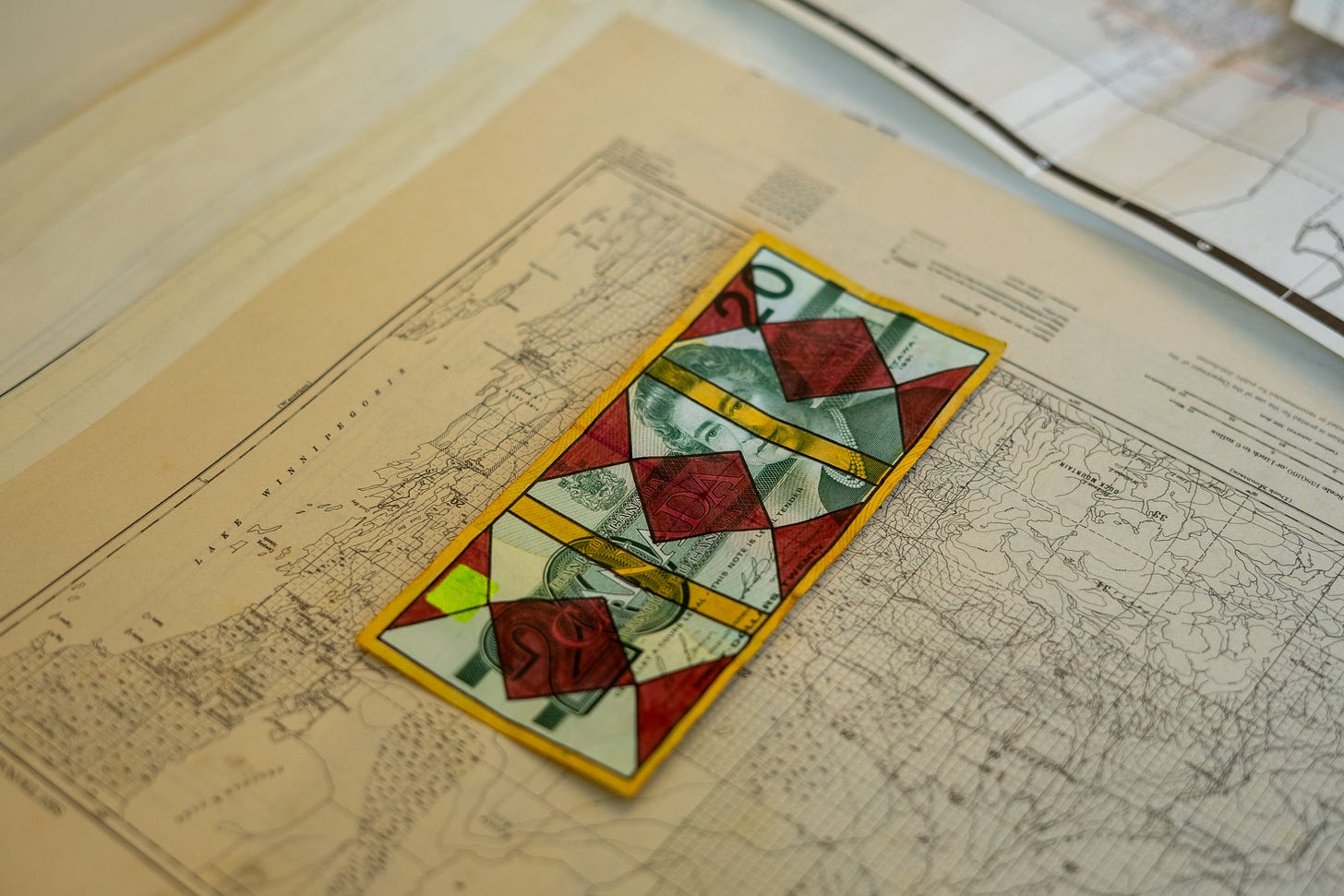

He started to explain some of the artwork he had done and he showed me a few more examples. The theme of this show was ledger art and as we were talking, he started to pull out some antique maps he had recently found, some dating back to the early 1900's. He plans on using these for upcoming shows or projects, and we spent some time flipping through admiring the pages that were now well over 100 years old. This played into many of my own fascinations, Canadian history, article preservation, and hand-drawn utilitarian art forms.

I unfortunately missed the show, but he had been telling me how he spent time talking to people coming through, explaining the pieces, and sharing the knowledge of the symbolism and designs he used in his interpretation of ledger art.

We used to have these… they're called winter counts. So winter counts used to keep track of the years. So if there's a prominent event that happened in a year, they used to be done on Buffalo hides, and they're circular, and it spirals out. So every year is a prominent thing. That's how we're able to count our winters and tell how much time has passed in between these significant events. And they're like a pictograph, almost, and it tells a story of something. But what happened was when we got put on our reserves and there was the RCMP and Indian agents, they apprehended a lot of that stuff. So they confiscated it, burned it, or sold it, probably across seas or wherever, and they took them. And we had no way of really recording what happened more. So there was ledgers or a piece of paper, banknotes that they would get or find, and then they would be able to draw on those. And then it turned into this art form. And it's more so in the prairies and in the plains that this happened.

And so with the ledgers and stuff like that, when they're able to do that, they're able to draw on those to still keep track of things. But because it looks like a book, it wouldn’t be confiscated. You know what I mean? So that's where that came from. And I got really interested in it and learning about it. And when I found these maps and stuff, I'm only looking for maps that are Alberta, Upper Montana, things like that. That would be in traditional Blackfoot territory. And so that's a lot of the work that I was trying to focus on, especially with the exhibition that we just did. I made sure to put Lethbridge and you can still see Vancouver on the map on both sides on a few of them because then that was my tie to home across these different places and stuff through Blackfoot Lodge designs. So being able to tie all that in. That's what I've been working with now. And it's been really meaningful to me because I really want to learn and continue that practice of painted lodges or painted designs and the stories behind them and the meaning and carry those forward in a little bit of a more contemporary way so that younger Blackfoot people can take those stories and then see themselves in that work and be able to carry on what our interpretation is of the motifs and stuff that are used.

As you've probably learned in listening to this conversation, this idea of following familial and cultural protocols is at utmost importance to Two Smudge, and at the end of our time together, he returned to this idea of protocol and expanded on some of the significance and careful stewardship of the symbolism and designs he uses.

There's protocol where we come from with teepees. Whoever puts it up, you don't leave it. In my old ways, if you left it, someone could go take it. They'll just take it because you're not taking care of it. Because especially when there's designs on teepees, there's a whole different complexity that comes into it because they get those designs. It's passed down, and we call transfers. So being transferred a design, there's responsibilities and protocol that comes with that. So you can only do certain things. That person has the right to that design. That's another reason why I only do components, especially with certain colorways or things, because I don't have the right to copy a design. I can reference the motif or the things that are more, I guess, general, but I don't have the right to go copy a design because I haven't been transferred the right from whoever else. Or they come from dreams. And there's a reason why that person gets that design, maybe like something in their life is happening or something's about to happen. And there's a lot of responsibility that that lodge holder, they have to follow and live a certain way and do certain things.It's not just something you get because you can get one or like, oh, I'm going to go paint that teepee Just because I want to, you have to have the right to even be able to paint on the teepee. And that transfer has to happen. And then once you have that design, you can have the right to paint, but then you need to be transferred that design. So it's a whole bunch of things that happen with over time. And I think that's been my end goal is to be able to work hard enough and live a good life so that I can one day have and have that opportunity to experience what that is.

We hung out for a little while longer as he and his fiancé shared some of their summer plans and we looked through more maps and his art.

As we wrapped up, he offered me a few gifts to take with me, and I felt so grateful for the gifts of knowledge and story, that the t-shirt and stickers were an abundance.

This story has been incredible to work on, and I thank Two Smudge for inviting me into his house and sharing his story. I am so excited to finally get to share it, I hope you enjoyed it.

If you’d like to follow Two Smudge on Instagram, you can do so here. He will be continuing to work on art for the foreseeable future and the best place to stay tuned will be through his Instagram.

If you’re enjoying this series, I ask that you subscribe to my Substack to be notified when new episodes are posted, or, you can now follow on Spotify. Oh, and if you can, find the little heart button, it means a lot!

As for every interview, I always ask the interviewee for two people who they’d like to see on this series; one local, and one “reach”.

Here is his suggestions:

Local: Kevin Lalune (@kevinlalune) - Fashion designer who “strives to merge utility with artistry—crafting garments that are both wearable and conceptually rich”. He went to school with Two Smudge and was living in Europe and is now back living in Vancouver.

Reach: Bobby Hundreds (@bobbyhundreds) - Co-founder of The Hundreds, and author of one of my favorite brand/culture books “This is Not a T-Shirt”, who, is actually on my personal “reach” list already!

Know someone who you think would really enjoy this interview, or this series in general? Maybe you can consider sharing using the button below.

Have a suggestion for someone you’d like to see featured on this series?

Share this post